Of Phones and Manuscripts

Reading time: 2 minsTwo years ago an article in Science Advances confirmed the presence of lapis lazuli, a blue pigment found mainly in Afghanistan, in the teeth of a nun who died in the 11th century. The various interpretations of that discovery and the discussions it spurred (among those about the role of women in the production of medieval books) were in itself fascinating and sometimes controversial.

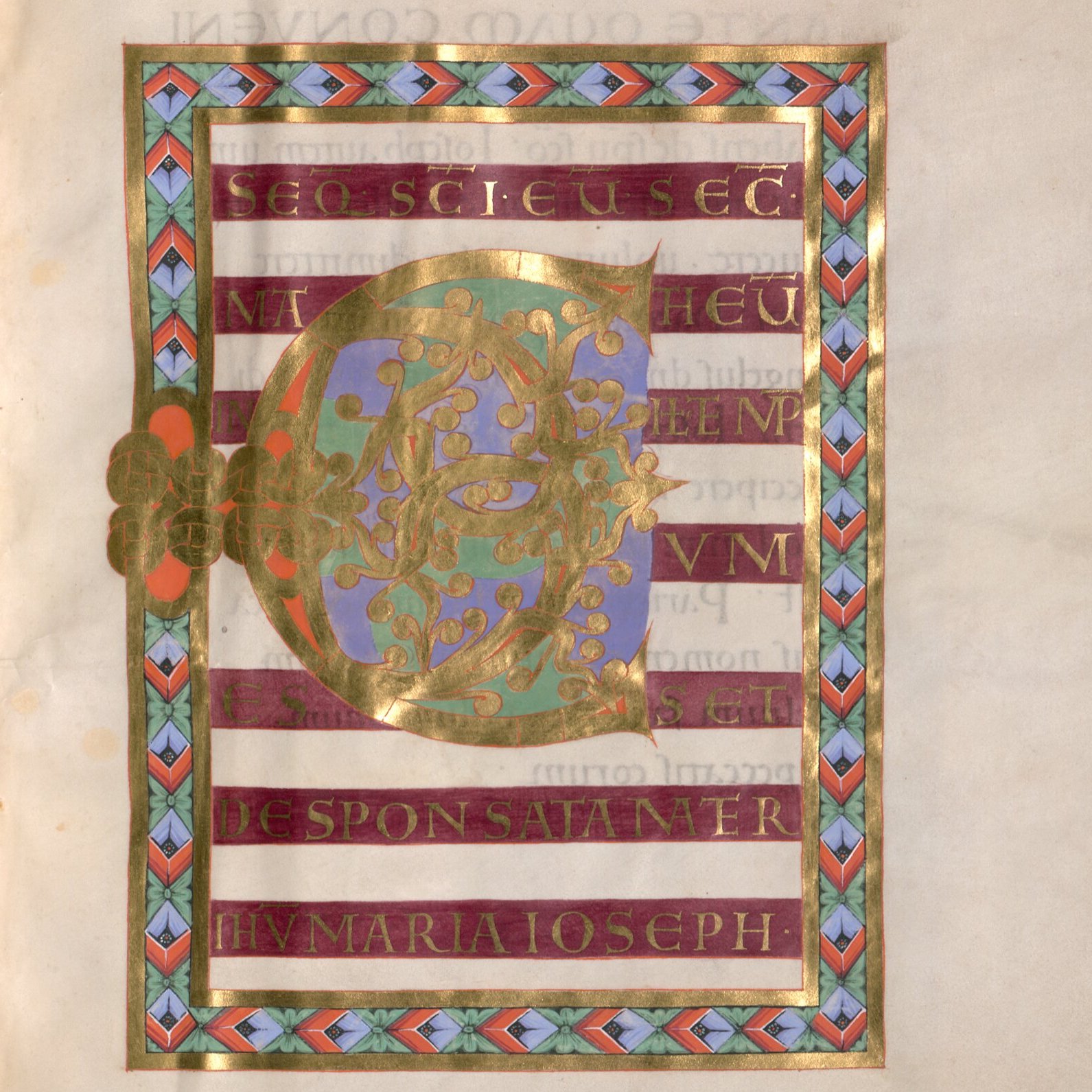

However, perhaps the most crucial consequence of this discovery was the momentary attention given to the raw materials needed to produce a medieval manuscript. Those resources were immense, especially if we talk about the more prestigious, illuminated manuscripts. Take the Pericopes of Henry II, BSB Clm 4452, made in the first decade of the eleventh century at the monastic scriptorium in Reichenau, in what is now southwestern Germany. This one book contains gold, silver, ivory, purple, indigo, malachite, minium and, least we forget, perhaps as many as 200 animal skins transformed into parchment.

Many of those were, in the Middle Ages, what we would call today rare elements: extremely difficult to obtain and finite resources that needed to be imported from far away - sometimes (most likely indirectly) India or Afghanistan. They made manuscripts extremely precious but also global objects par excellence. Obtaining those materials was a result of global connections but also, even if we do not see it at the first glance, sometimes of violence, extortion, and imbalance of power. Just like tellurium, lithium, cobalt, manganese or tungsten in the phone the you are perhaps now holding in your hand and using to read this post. The extraction, processing and transport of those materials requires global connections, great resources, and is a huge stress to the global economy. They also make your phone, just like the Pericopes of Henry II, a truly global item.

Your phone and the Pericopes of Henry II share then many surprising similarities. They are both objects made from rare materials, both are text technologies, and both can dazzle your eyes with thousands of colours. But they are also different. For your phone, even though it uses such rare and finite resources is an object to be, ultimately, thrown away. A medieval manuscript is an object to be kept - and re-used. The ivory and the medallions at the cover of Clm 4452, perhaps also most of its gold, were re-used and repurposed. Many other medieval manuscripts were scraped, rewritten, rebound.

There is a lesson in sustainability here: the Middle Ages were an epoch centred in many ways on reuse. For generations this was seen as a drawback, as a fault of the whole epoch, deeming it unoriginal and derivative. But it is time to change this narrative and see what we can learn from it. A culture of re-use, of recycling and reforging existing resources, can derive valuable lessons from the medieval past. Perhaps most importantly that one cane be uncompromisingly, original and creative and yet practice re-use at almost every step of the way.

Cite this post:

Fafinski, Mateusz "Of Phones and Manuscripts." History in Translation (blog), 16 Jul 2021, https://mfafinski.github.io/Phones_manuscripts/.