Governing through Giving. A Sneak Peek

Reading time: 5 minsFollow me on twitter @Calthalas

It’s good to be a king, sort of

I am now working a lot on uncertainty in historical data. And of course I could not pass the occasion to combine this research with my all time favourite - charters!

While my long-standing project on an interactive atlas of early medieval charters in Britain is still very much in development (although one can expect more frequent updates soon) here is a little sneak peek into it. In order to show that charters are a very dynamic resources let us talk itineraries.

Some royal itineraries are extremely detailed and allow us to trace the royal progress in great detail. But in case of the pre-1066 rulers of England such data is simply not accessible. What we call “itineraries” are very often just singular locations and those often conjectured. German has a great term for it, that works so much better for such uncertain data than “itinerary”: “die Aufenthaltsorte”. The whereabouts.

The Royal Whereabouts

The idea of governing through giving is one of the crucial elements of early medieval governance.1 It embodies one of the crucial actualisations of the early medieval do ut des - I give, so that you may give. This process is much more complicated than a simple reciprocal relationship between the king and the landowning class and does not always entail a transfer of land. It actually embodies the role of the king as the regulating factor in the realm. Giving as a king is becoming a king. Kingship is a process not a state. And the main sources to this process, the main emanation of this activity that we have, are the charters.

If we look at the reign of Edward the Confessor we can attempt a simple reconstruction of “the royal whereabouts”. Those are very often reconstructed on the basis of the place of issue of royal charters.

The importance of the proximity relationship between the king and the ruling class is well illustrated if we superimpose those locations with the locations of the estates that are given away.

When we look at this animation we can immediately spot the patterns of proximity. They make sense, when we think about the process of petitioning for a charter and the itinerant nature of medieval kingship. But we can also see how certain places are associated with more grants, perhaps, if we were so bold to hypothesise, because of their role and significance (and their connectivity). We can also notice the hotspots of Edward’s reign. At the very beginning, when giving in order to facilitate becoming a king is especially pronounced; and after the turbulent years 1051-52.

And here we have it, a reign in charters:

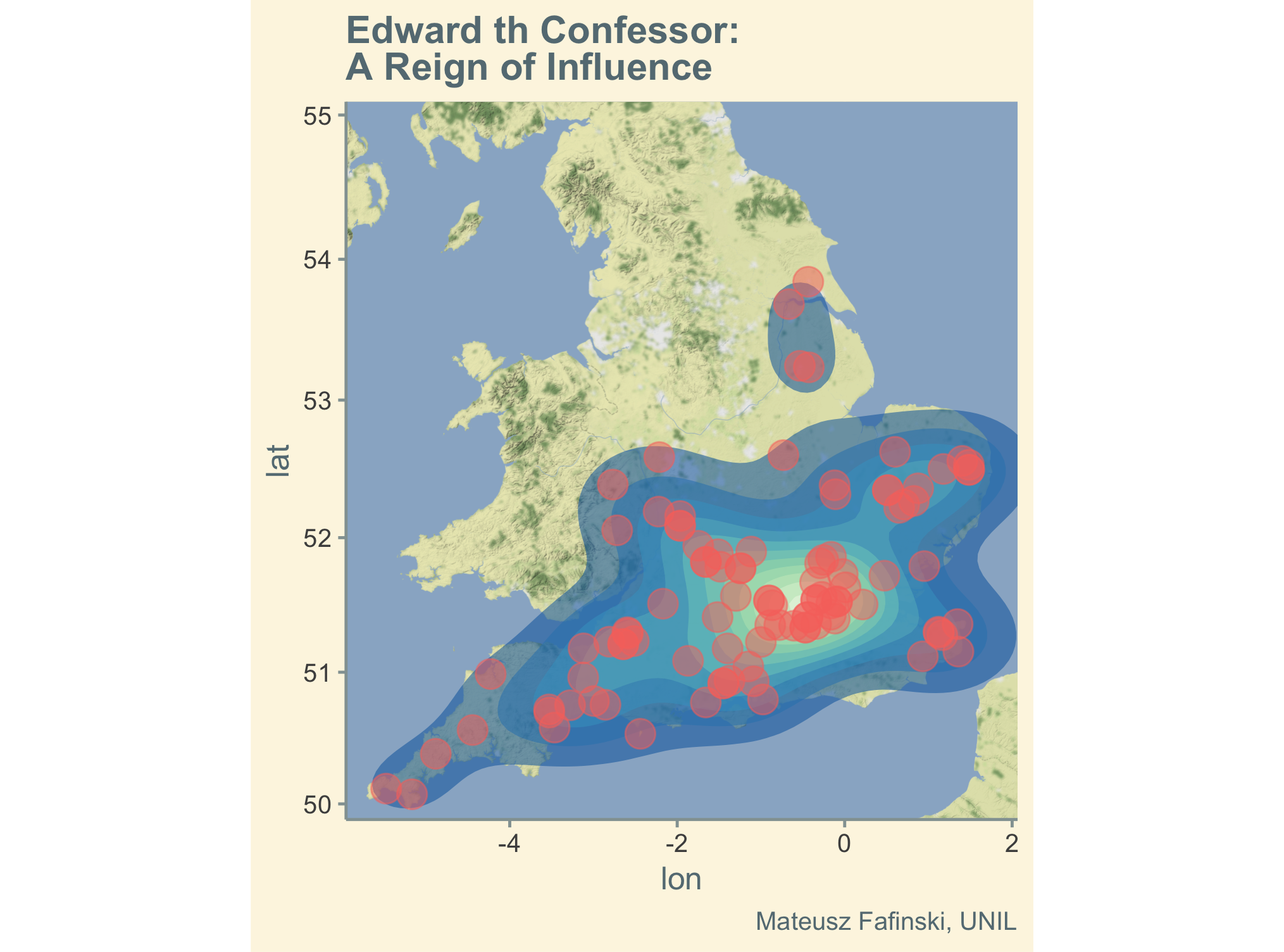

Perhaps we can also start thinking differently about the geographical extents of early medieval reigns (as opposed to kingdoms, for those would be two different concepts). Based on our (incomplete!) data, Edward’s reign of influence would look something like that:

A note on methodology

This is just a little snippet of what “animated charters” can do and what hopefully the atlas of early medieval charters in Britain will enable. Of over 160 writs and charters only the charters with an identifiable estate or benefice location are inlcuded, bringing their number to little over a 100. After excluding the obviously spurious charters we arrive at little over 80. Of course we can never forget loss: we have lost most of the charters north of the Humber and many charters are lost. In a way, we are mapping here not only our surviving charters but also our narrative about Edward’s reign. There is a high level of uncertainty to be modelled and factored in when making (and interpreting) those maps.

Edward’s itinerary is based on the work of Oleson and the charter data. I have included the S1061 from 1027 x 1035, which is of contested authenticity, but which Keynes has seen as possibly being not spurious. The little animation that you are seeing is done in R and moves thanks to the gganimate package.

Bibliography

Barlow, Frank, Edward the Confessor (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1970)

Bernhardt, John W., Itinerant Kingship and Royal Monasteries in Early Medieval Germany, C.936-1075 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002)

Davies, Wendy, Paul Fouracre, The Languages of Gift in the Early Middle Ages (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010).

———, The Settlement of Disputes in Early Medieval Europe (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992)

Keynes, Simon, ‘The Æthelings in Normandy’, Anglo-Norman Studies, 1991, 173–205

Kjaer, Lars, The Medieval Gift and the Classical Tradition (Cambridge University Press, 2019)

Maddicott, JR, ‘Edward the Confessor’s Return to England in 1041’, The English Historical Review, 119 (2004), 650–66 https://doi.org/10.1093/ehr/119.482.650

Molyneaux, George, The Formation of the English Kingdom in the Tenth Century (Oxford University Press, 2015)

Oleson, Tryggvi J., The Witenagemot in the Reign of Edward the Confessor (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1955)

Problems and Possibilities of Early Medieval Charters, ed. by Jonathan Jarrett and Allan Scott McKinley, International Medieval Research (Turnhout: Brepols Publishers, 2013)

Stafford, Pauline, Queen Emma and Queen Edith: Queenship and Women’s Power in Eleventh-Century England (London: Wiley, 2001)

-

Although I am aware that the very idea of “governance” in the Early Middle Ages is seen as controversial. ↩

Cite this post:

Fafinski, Mateusz "Governing through Giving. A Sneak Peek." History in Translation (blog), 03 Apr 2020, https://mfafinski.github.io/Governing_through_giving/.