The Face of an Emperor

Reading time: 11 minsHeraclius (c. 575 – February 11, 641) must be one of my favourite emperors. His reign is the story of Late Antiquity and of its global scope in a nutshell. It also teaches us that we need a broader, more global perspective to uderstand our period. An Armenian who rose to the throne in a rebellion against Phocas, he lost half the empire to the Persians, regained it all in (vain)glory only to see it fall into the hands of the ascendant Muslim armies and who became a hero of a Swahili epic a thousand years after his death. As it turns out the tragic quality of his life story was not lost to his contemporaries and one particular drawing might tell us a lot about how they have viewed him. We just need a bit of a broader perspective to see it.

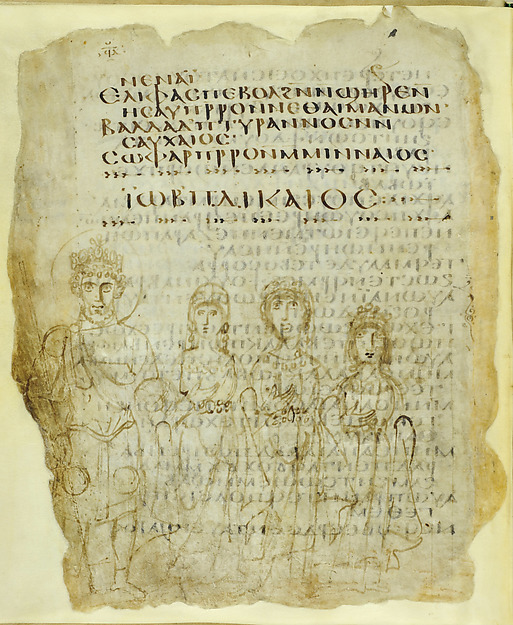

In the collections of National Library in Naples we can find a small Coptic manuscript from the 5th C., containing a version of the Book of Job (MS.I.B.18). On the last folio, in an empty space, somebody later on drew a group portrait. Four figures, one male and three females, in rich garments, looking directly at the reader.

The figure with a halo is regal in statue: he wears a crown, a cuirass, high military boots and a paludamentum (a military cloak associated with the imperial garb). His beard is rounded, well trimmed and his hair is worn short. In his right hand he carries a kind of sceptre (that some authors have identified as a lance) and in his left an imperial orb, sphaira. If we had any doubts about his identity within the manuscript there is an inscription above saying “Job the Just”: ⲇⲓⲕⲁⲓⲟⲥ, the term being a direct borrowing from Greek δίκαιος.

The three women are smaller of statue but also richly dressed. One can also notice that there is just a little bit less detail in their drawings. The first two female figures (counting from the left) have what Breckenridge called “spherical coiffures” which are fastened by snoods and that in turn might indicate that they are married.

Who are they? This is not the Job that most readers are accustomed to. He is a king, a royal figure. On account of similarity of the looks of the male figure to coin portraits of Heraclius a theory appeared that the drawing depicts actually the emperor and his family. Richard Delbrück has dated the drawing to around 620s on the basis of identifying the women as Martina, emperor’s niece and second wife (the marriage was to be a scandal - it was against the laws prohibiting incest); Epiphania the Elder, emperor’s sister and mother-in-law (this has to be Delbrück’s error, repeated often in English-speaking literature about the miniature: Heraclius’ sister was called Maria, his mother was called Epiphania) and lastly Eudoxia, daughter of the emperor from the first marriage (crowned Augusta already as a baby in a dynastic-security move). A portrait of power - this is the emperor, his sister and the empresses.

So who is he? Is he Job or is he Heraclius? The caption says one thing the visual similarity another. The reality is quite complicated. The Coptic version of the Book of Job contains a last chapter, taken from the Septuagint, omitted in the Vulgate:

This man hath been described in the Syriac book as having dwelt in the land of Ausis, on the borders of Idumea and Arabia: and his name before was Jobab; and he took an Arabian wife, and she bare him a son whose name was Enon. And his own father was Zara, who was of the sons of Esau, and his mother was Bozora, so that he was the fifth after Abraam. And these were the kings who reigned in Edom, the country which he also ruled over: the first was Balak the son of Beor, and the name of his city was Dennaba: after Balak, Jobab, who is called Job: after him Asom who was the governor out of the country of Thaeman: and after him Adad the son of Arad, who destroyed Madiam, in the field of Moab; and the name of his city was Keththem. And his friends who came to him, Elisaph, a son of one of the sons of Esau the king of the Thaemanites, and Baldad, the king of the Sauchaeans, and Sophar, the king of the Minaeans.

(Tattam 1843, p. 182-183)

This equates Job with a king of Edom, Jobab. If this were the case we are looking here not at an emperor, but on an Old Testament king, who happens to also be Job. This interpretation has been put forward already in 1942 by Otto Kurz, who forcefully reputed any link with Heraclius, writing that since it can only be one or the other, it has to be just Job. Since Job also happened to have three daughters: Jemimah, Keziah and Keren-Happuch (Job 42:14) that would seem to be the final answer to the identity question.

The web of analogies and interpretations does not end here: there is another Coptic link between royalty and Job: The Testament of Job. The earliest manuscript of this piece of intertestamental literature, written sometime between 1st century BC or the 1st century AD, is in Coptic and comes from the 4th century AD. In it, Job is the king of Egypt (interestingly it also gives a much more prominent role to Job’s wife, named Stidos and contains views on God’s mercy that seem quite close to later, Christian beliefs, accentuated by later Christian interpolations). The image of Job driven into the mud, old and despairing is simply a result of Europo-centric view of that character. Other traditions, ignored (Testament of Job was virtually unknown in the “West” until published in 1833) have a very different view of him. In the Testament he is called “Conqueror in Many Contests”. He is a tried and tested, but ultimately victorious king.

And by whom, you might ask, is Job taunted the most in the Testament of Job? By no other than the king of Persia:

Then the devil got to know my heart and turned into the king of Persia to (deceive) me. And he came to my city and gathered his servants and said to them: “This man Job […] he totally destroyed God’s church. I shall pass judgement on him against his deeds what he has done to the great God. All of you assemble, capture him and take all this wealth which is inside the house and also outside”.

(Haralambakis 2007, p. 197)1

The similarity with calamities that Heraclius suffered from hands of the Persians are striking.

So is that it? Is this just a picture of a biblical king that the Coptic scribe drew on an empty space? Not necessarily. What is perhaps crucial and escaped the critics like Kurz is the ability of Late Antique people to think in so many layers. The imperially-clad figure on the left can simultaneously be Job, Joab, king of Egypt, and emperor Heraclius. He is the king that went through hell to remerge victorious. He was taunted by the king of Persia, he “destroyed the God’s church” (no doubt a Christian interpolation). This tradition was in all probability well-known to the Coptic scribe, who drew the portrait. Parallels were numerous and easy to spot.

Interestingly this could allow us to date the drawing quite precisely and slightly differently than Delbrück. To fit the analogy Heraclius must have already been victorious in the war against Persia, but still not be defeated by incoming Muslim armies. Moreover in the image he is wearing still his distinctive rounded beard known to us from the earlier coins.

Heraclius. Dumbarton Oaks Coin Collection

Heraclius. Dumbarton Oaks Coin Collection

Heraclius I and Heraclius Constantinus. Münzkabinett SMB

The issues from late 630s will have him have the long beard of a patriarch. Therefore if this was meant to be Heraclius-Job, the drawing must have been made sometime between c. 630 and c. 635. After that date analogy starts falling apart.

Heraclius’ relationship with the Church in Egypt was complicated at best. His probably sincere attempt at compromise was ultimately rejected, but nevertheless his rule was probably seen as better than the Persian yoke. His persecution of the Monophysite party would fall only after the failure of his compromise idea of ecthesis, a bizarre compromise, which seemed to have depended simply on trying to ignore most problems.2 It is conceivable that for a short time after reconquest of Egypt from Persian hands he might have been seen by a Coptic scribe as Job the Just, Conqueror in Many Conquests.

Look again at his face. He is gentle, big-eyed, groomed. But there is a hint of grimace on his lips. The facial features of the women accompanying him are subtly over-the-top - eyes too small or too big, noses large. Is this maybe also a caricature? Far from being a straightforward allegorical image it might be a way for the Monophysite scribe to criticise Heraclius’ incestous family. There is a hint of mockery there. The emperor has many faces.

Therefore we do not need to identify the figure in a binary way. He is simultaneously Job and Heraclius. He is the Job-King of Coptic tradition, persecutor of the true believers, who through an attempt at compromise and repelling of the Persian threat, temporarily (for us - the author of the drawing might have thought that no further calamity would befall the emperor and that he will not try to enact his compromise by force) redeems himself.

Heraclius was destined to have a long afterlife in later Muslim Egypt and Africa - he would be seen in those traditions as a just but flawed ruler. His non-binary image was to have a lasting legacy. It is worth here to mention the Kyuo kya Hereḳali - The Book of Heraclius a Swahili epic written in 1728 telling the story of Byzantine-Muslim wars, in which Heraclius emerges as a just, but ultimately defeated emperor.

Heraclius defeating the Persians. Tapestry from 8th C. Egypt, Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Heraclius defeating the Persians. Tapestry from 8th C. Egypt, Victoria and Albert Museum, London

The drawing from MS.I.B.18 is a kind of a gift. It shows us that binary interpretations might seem to be easier but ultimately might also obscure the multilayered meanings. It also stresses the need to view Late Antiquity from a more global, broader, non-Western perspective. This might be the only extant 7th C. political caricature that we know of and it was made in Africa, under a Coptic text and could have been influenced by a Jewish text, that survives in Coptic, Greek and Old Church Slavonic manuscripts. Global Byzantium if ever there was one.

Bibliography

Ainalov, Dmitrii Vlasevich. The Hellenistic Origins of Byzantine Art. Edited by Cyril Mango. Translated by Elizabeth Sobolevitch. New Brunswick, N.J. : Rutgers University Press, 1961.

Breckenridge, James D. ‘Drawing of Job and His Family Represented as Heraclius and His Family’. In Age of Spirituality: Late Antique and Early Christian Art, 3rd to 7th Century ; Catalogue of the Exhibition at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, November 19, 1977, through February 12, 1978, edited by Kurt Weitzmann and Metropolitan Museum of Art. Princeton: Princeton Univ. Pr, 1979.

Delbrück, Richard. Die Consulardiptychen Und Verwandte Denkmäler. Studien Zur Spätantiken Kunstgeschichte 2. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 1929.

Haralambakis, Maria. The Testament of Job: Text, Narrative and Reception History. Library of Second Temple Studies 80. London: Bloomsbury, 2012. Kaegi, Walter Emil. Heraclius Emperor of Byzantium. Reprinted. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 2007.

Kühnel, Gustav. ‘Heracles and the Crusaders: Tracing the Path of a Royal Motif’. In France and the Holy Land: Frankish Culture at the End of the Crusades, edited by Daniel H. Weiss and Lisa Mahoney, 63–76. Parallax. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2004.

Kurz, Otto. ‘An Alleged Portrait of Heraclius’. Byzantion 16, no. 1 (1942): 162–64.

Tattam, Henry. The Ancient Coptic Version of the Book of Job the Just. W. Straker, 1846.

Cite this post:

Fafinski, Mateusz "The Face of an Emperor." History in Translation (blog), 10 Feb 2018, https://mfafinski.github.io/Heraclius/.